Which Animal Is Most To Blame For The Loss Of Forests In Southwest Asia And North Africa?

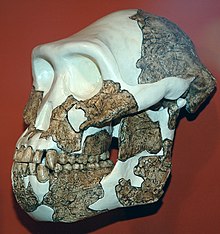

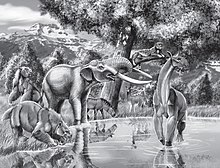

Recreation of a scene in late Pleistocene northern Kingdom of spain, by Mauricio Antón

Pleistocene megafauna is the ready of large animals that lived on Earth during the Pleistocene epoch and became extinct during the Quaternary extinction effect. Megafauna are any animals with an adult body weight of over 45 kilograms (99 lb).

Pleistocene megafauna include the direct-tusked elephant, cavern bear (Ursus spelaeus), interglacial rhinoceros (Stephanorhinus), heavy-bodied Asian antelope (Spirocerus), Eurasian hippopotamuses, woolly rhinoceros, mammoths, giant deer, sabre-toothed cat (Homotherium), cavern lion, and the leopard in Europe.

Listing of Pleistocene megafauna [edit]

| Species | Continent |

|---|---|

| Gorgopithecus | Africa |

| Dinopithecus | Africa |

| Cercopithecoides | Africa |

| Paranthropus | Africa |

| Australopithecus | Africa |

| Megalonyx | North America |

| American lion | N America |

| Glyptotherium | Northward America |

| Aiolornis | North America |

| Woolly mammoth | Eurasia |

| Steppe mammoth | Eurasia |

| Woolly rhinoceros | Eurasia |

| Procoptodon | Australia |

Paleoecology [edit]

The final glacial menstruation, normally referred to every bit the 'Water ice Age', spanned 125,000[2] to 14,500[3] years ago and was the nigh contempo glacial period within the current ice age which occurred during the final years of the Pleistocene epoch.[two] The Ice Age reached its peak during the terminal glacial maximum, when ice sheets commenced advancing from 33,000 years BP and reached their maximum positions 26,500 years BP. Deglaciation commenced in the Northern Hemisphere approximately 19,000 years BP, and in Antarctica approximately fourteen,500 years BP which is consequent with evidence that this was the chief source for an abrupt rise in the sea level xiv,500 years ago.[iii]

A vast mammoth steppe stretched from the Iberian peninsula beyond Eurasia and over the Bering country bridge into Alaska and the Yukon where information technology was stopped by the Wisconsin glaciation. This land bridge existed because more than of the planet'southward water was locked up in glaciation than now and therefore the sea levels were lower. When the sea levels began to rise this bridge was inundated around eleven,000 years BP.[4] During the last glacial maximum, the continent of Europe was much colder and drier than it is today, with polar desert in the north and the residuum steppe or tundra. Forest and woodland was almost not-real, except for isolated pockets in the mountain ranges of southern Europe.[five]

The fossil evidence from many continents points to the extinction mainly of large animals at or most the cease of the last glaciation. These animals have been termed the Pleistocene megafauna. Scientists frequently define megafauna every bit the set of animals with an developed body weight of over 45 kg (or 99 lbs).[half-dozen] Beyond Eurasia, the straight-tusked elephant became extinct between 100,000 and 50,000 years BP. The cavern bear (Ursus spelaeus), interglacial rhinoceros (Stephanorhinus), heavy-bodied Asian antelope (Spirocerus), and the Eurasian hippopotamuses died out between 50,000 and xvi,000 years BP. The woolly rhinoceros and mammoths died out between 16,000 and xi,500 years BP. The giant deer died out later on eleven,500 BP with the last pocket having survived until about vii,700 years BP in western Siberia.[7] A pocket of mammoths survived on Wrangel Island until 4,500 years BP.[8] Equally some species became extinct, so too did their predators. Among the top predators, the sabre-toothed true cat (Homotherium) died out 28,000 years BP,[9] the cavern lion xi,900 years BP,[x] and the leopard in Europe died out 27,000 years BP.[eleven] The Late Pleistocene was characterized by a series of astringent and rapid climate oscillations with regional temperature changes of upwards to 16 °C, which has been correlated with megafaunal extinctions. In that location is no evidence of megafaunal extinctions at the acme of the LGM, indicating that increasing cold and glaciation were not factors. Multiple events announced to also involve the rapid replacement of one species by one within the same genus, or one population by another inside the same species, across a broad area.[12]

The ancestors of modern humans first appeared in E Africa 195,000 years agone.[13] Some migrated out of Africa sixty,000 years agone, with one group reaching Central Asia l,000 years agone.[14] From there they reached Europe, with human remains dated to 43,000-45,000 years BP discovered in Italy,[15] Britain,[xvi] and in the European Russian Arctic dated to 40,000 years ago.[17] [18] Another group left Central Asia and reached the Yana River, Siberia, well above the Arctic circle, 27,000 years ago.[19] Remains of mammoth that had been hunted past humans 45,000 YBP have been found at Yenisei Bay in the central Siberian Arctic.[20] Modern humans and so fabricated their manner across the Bering land bridge and into Northward America between 20,000 and 11,000 years agone, after the Wisconsin glaciation had retreated only before the Bering state bridge became inundated past the sea.[21] However, there remains no consensus amid scholars on the timing of homo migration into the Americas.[22] In the Fertile crescent the first agriculture was developing eleven,500 years agone.[23]

Ecological consequences of megafaunal extinctions [edit]

Community and ecosystem changes [edit]

Megafauna extinctions resulted in global changes to ecosystem structure and part.[24] [25] Extinction of megafauna broadly restructured ecological communities, reducing the strength of biotic drivers.[26] Some evidence, however, suggests that vegetation changes preceded megafaunal extinctions.[27] Evidence from fossil pollen indicates that megafaunal extinctions may have resulted in the development of novel plant communities,[25] [28] and altered fire regimes on a global scale.[25] [28] [29] Some hypothesize that forbs in mod grasslands are adjusted to disturbance by large herbivores on former mammoth steppes, and are currently in decline due to the extinction of Pleistocene megafauna.[thirty] [31] In Europe, testify from the pollen tape suggests that megafauna promoted open vegetation with shifting mosaics of forest and grassland,[31] nonetheless this hypothesis is debated.[28] In the Yukon region of Canada, the decline of Mammuthus and Equus may have contributed to the development of woody flora.[32] The extinction of megafauna also affected mutualist species, resulting in co-extinctions.[33] Some argue that modern ecosystems tin can be understood by considering the effects of extinct megafauna.[31] [28] [33]

Anachronistic plants [edit]

Some extant plants accept adaptations resulting from interactions with Pleistocene megafauna, including defenses against Pleistocene megaherbivores,[31] [33] and large fruits adjusted to dispersal by megaherbivores.[28] [33] Such species are termed anachronistic plants.[31] Megafaunal extinction caused the turn down of Cucurbita species which relied on megaherbivores for dispersal.[34] Some argue that plant adaptations to megafauna resulted in traits that immune for domestication.[35] [34]

Furnishings on climate [edit]

Megafaunal extinction may likewise resulted in global cooling of the Earth's climate due to reduced methane emissions from megaherbivores and increased woody vegetation associated with reduced trampling and browsing.[24] Smith et al. suggest that megafaunal extinctions in the Americas contributed to the Younger Dryas cooling result.[36]

Extinction [edit]

Four theories accept been advanced every bit likely causes of these extinctions: hunting by the spreading humans (or overkill hypothesis, initially developed by geoscientist Paul S. Martin),[37] the change in climate at the stop of the last glacial catamenia, disease, and an extraterrestrial impact from an asteroid or comet.[38] [39] [40] These factors are not necessarily sectional: any or all may have combined to cause the extinctions. Of these, climatic change and the overkill hypothesis[41] have the about support,[42] with evidence weighing towards the overkill hypothesis.[43]

Although not mutually exclusive, which factor was more important still remains contested.[44] [43] Where humans appeared on the scene, megafauna went extinct;[45] [46] but at the same time, the climate was likewise warming. Large body size is an adaptation to colder climes, so a warming climate would have provided a stressor for these large animals; however, many beast simply evolved a smaller body size over fourth dimension.[47] There is overwhelming archaeological evidence suggesting humans did indeed hunt some or many of the now extinct species, such equally the mammoth in Due north America;[48] on the other hand, there is non much prove for this in Australia for most of the megafauna that went extinct at that place,[41] aside from a large bird.[49] A 2017 report in Nature Communications asserts that humans were the primary driver of the extinction of Australian megafauna.[50] One newspaper arguing genetic prove shows there were many species of megafauna that went extinct "invisibly" argues that this means climatic change was primarily responsible.[44]

Regions afflicted [edit]

Africa [edit]

Groundwork and scope [edit]

Extant African primates, clockwise from top: chimpanzee (Pan), male person human (Homo sapiens), vervet monkey (Chlorocebus pygerythrus), bushbaby (Galago sp.), mount gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei), and female human being

The proportion of extinct large mammal species (more than or equal to x kg) in each TDWG state during the last 132 000 years, merely counting extinctions earlier than chiliad years

Australopithecus afarensis (Johanson & White, 1978) - fossil hominid from the Pliocene of eastern Africa. (replica, public display, Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Cleveland, Ohio, USA)

While N America was most notably impacted by the Pleistocene Megafaunal extinction, Eurasia, Africa and the Insular regions were also affected and experienced some extinction towards the finish of the Pleistocene period. Megafaunal losses are poorly understood on continental Africa during both the Belatedly Pleistocene and the Holocene periods. During the tardily Pleistocene and early Holocene period an estimated breadth of 24 large mammal species, of greater than 45 kg, were lost from continental Africa. These losses are best understood to have occurred between 13,000 and 6,000 years ago. The species of megafauna which were lost in continental Africa are best understood to have been grazers who lived on grasslands. However, other sources written report that over 27 species were lost in the last meg years. Sources vary in the breadth of the issue, withal it is clear that pregnant biodiversity loss occurred in Africa.

Acheulean polyhedron in quartzite that proceeds from a superficial site in the Valladolid province (Spain), in the valley of Douro river.

Acheulean Levallois chip that gain from a superficial site in the Zamora province (Spain), in the valley of a tributary of Douro river.

Anthropogenic involvement [edit]

At sites in Africa such every bit Olduvai, Olorgesailie, Kariandusi, Hopefield, Islmilia, and the Vaal River gravels well-nigh genera found were found in stratigraphic clan with manus tools wielded past early man ancestors.[51] These artifacts were from Acheulean origins. Acheulean tools include handaxes made from stone. These hand tools were fabricated with a distinctly pear shaped morphology. Homo erectus was thought to wield these hand tools for a variety of purposes. Hand axes could be used to butcher and pare game, cut, chop, scrape, cut other instruments, digging in soil, cut wood, cutting establish material.[51] These tools were get-go discovered in 1847.[51] These handaxes have been discovered on multiple continents including Southern Africa, Northern Europe, Western Europe and the Indian sub-continent. These Acheulean tools were constitute to have been being produced and utilized for roughly a million years.[51] The earliest Acheulean artifacts were discovered in Africa to have existed for over 1.6 million years agone whereas the earliest Archulean tools are thought to take existed in Europe equally early on as 800,000 years ago.[51] These hand axes measure 12–20 cm long. At that place is notable difference in the size, quality and efficacy of these tools depending on the workmanship of the crafter.

Arguments have existed regarding whether these early humans could take contributed significantly to megafauna extinction in Africa, Eurasia, and North America utilizing stone tools such as the Archulean paw tools which accept been discussed. Information technology is of import to note that these analyses are considered incomplete past many contemporary scholars.[52] Nevertheless, despite the lack of scientific consensus surrounding this theory, this is being practical to gimmicky biodiversity losses.[53]

"A growing body of literature proposes that our ancestors contributed to large mammal extinctions in Africa long before the appearance of Homo sapiens, with some arguing that premodern hominins (e.g., Homo erectus) triggered the demise of Africa's largest herbivores and the loss of carnivoran diversity. Though such arguments have been around for decades, they are at present increasingly accepted by those concerned with biodiversity reject in the present-twenty-four hours, despite the most complete absence of critical discussion or argue. To facilitate that process, hither nosotros review aboriginal anthropogenic extinction hypotheses and critically examine the data underpinning them. Broadly speaking, nosotros show that arguments fabricated in favor of aboriginal anthropogenic extinctions are based on problematic data analysis and interpretation, and are substantially weakened when extinctions are considered in the context of long-term evolutionary, ecological, and environmental changes." [53] At the present moment - according to this source, there is no definitive empirical bear witness to advise that hominins have had widespread touch on the biodiversity of Pleistocene Africa.

Other sources propose alternate hypotheses: "To our knowledge, the primeval proposal of ancient hominin impacts in Africa tin can be traced to J. Desmond Clark's (1959) overview of southern African prehistory. Referring to a handful of large herbivores whose last appearances in southern Africa are now known to range in age from ∼1 Ma to the onset of the Holocene (Brink et al., 2012; Faith, 2014; Klein et al., 2007), including Stylohipparion (= Eurygnathohippus cornelianus), Griquatherium (= Sivatherium maurusium), and Homoioceras (= Syncerus antiquus), Clark (1959:57) suggested that "[t]heir concluding extinction may well take been due to human'due south improved methods of hunting these overspecialized and probably clumsy beasts." Clark did not specify which hominin species was to blame, simply from the evidence available to him at the time, it was articulate that at least some of these extinct taxa (e.g., Stylohipparion and Griquatherium) disappeared long earlier the Pleistocene-Holocene transition (Clark, 1959:54) and were associated with hominins that preceded the emergence of H. sapiens, including H. heidelbergensis (Drennan, 1953)".[54] This discussion of Megafaunal losses in Africa during the Pleistocene flow would suggest that anthropogenic influence could have been a significant impetus for extinction.

Another hypothesis suggests a more than environmentally focused cause for the megafaunal extinction in Pleistocene Africa, "The current lack of prove (for hominin attributed extinction) does not forestall it from being produced in the futurity, though nosotros are not optimistic that it will be. Looking to the last ∼100,000 years-a time interval encompassing massive demographic and technological change among homo populations-it is clear that African megafaunal extinctions are readily explained past environmental changes (Faith, 2014). In particular, grassland herbivores disappeared following alterations in the structure, distribution, or productivity of their habitats (Faith, 2014), consistent with broader changes in herbivore customs limerick spanning the last one Myr (Organized religion et al., 2019)".[55] Environmental factors implicated in this explanation include structure, distribution and biological productivity of the environment. This caption minimizes human impact and emphasizes ecology factors.

African Pleistocene megafauna losses [edit]

African primate species from the Early Eye Pleistocene (ane.0-2.0 1000000 years ago) included Gorgopithecus, Dinopithecus, Cercopithecoidea, Australopithecus, Paranthropus, Telanthropus, Parapapio. Primates that existed during the Late Heart Pleistocene extinction period (100,000 years) included Semnopithecus. Living genera in Africa include Pan, Gorilla and Mandrillus. African Carnivora from the Early Centre Pleistocene included Lycaon, Megantereon, and Homotherium. Carnivores that existed during the Late Middle Pleistocene extinction period included Machairodus.[56] Living genera in Africa include Acinonyx, Panthera, Hyaena, and Crocuta. Interestingly, no Tubulidentata existed during the Early on Heart or Late Middle Pleistocene periods. However, Orycteropus is included in the living African genera. Similarly no Hippopotamidae existed during the Early Middle or Late Eye Pleistocene periods. Yet, Hippopotamus and Choeropsis are nowadays in the living African genera. Bovidae from the Early Middle Pleistocene include Pultiphagonides and Numidocapra. Bovidae that existed during the Tardily Centre Pleistocene extinction period included Homoioceras, Bulcharus, Pelorovis, Lunaloceras, Megalotragus, Makapania and Phenacotragus. Living Bovidae genera include Tragelaphus, Taurotragus, Syncerus, Cephalophus, Kobus, Redunca, Hippotragus, Oryx, Addax, Damaliscus, Alcelaphus, Beatragus, Connochaetes, Aepyceros, Litocranius, Gazella, Eudorcas, Nanger, Capra, Ammotragus.[57]

The summary of mammalian megafaunal extinction and survival can be discussed too comparing Africa and North America. Living genera (50 kg+) in Africa include twoscore and xiv in the US and Canada (Due north America). Later Pleistocene extinction genera include 26+ in Africa and 35 in the United states and Canada. Before Pleistocene extinction genera include nineteen in Africa and thirteen in the US and Canada. Later on Pleistocene Megafaunal Extinction Intensity was 39% for Africa, and 71% for the US and Canada. It is evident through this analysis that North America underwent a more intense subsequently Pleistocene Megafaunal Extinction.[ citation needed ]

Contrasting Africa's losses with Northward America [edit]

The charge per unit of extinction in the Pleistocene period between Africa and North America shows striking differences. In America, an estimated 35 genera of large mammals disappeared at the cease of the Rancholabrean catamenia. About of these animals were lost within the last 12,000 years. However, in the preceding ane to two million years earlier the finish of the Rancholabrean menstruation, an estimated 13 genera of megafauna were lost. This may be attributed to a poor understanding of fauna that existed before to this flow. To compare this charge per unit of megafaunal loss with Africa, the differences between the earlier, centre and later Pleistocene faunal losses are less desperate to compare. In the outset 1.v million years 19 megafaunal genera were lost. Within the last 100,000 years 26 or more than genera were lost. This charge per unit of megafaunal extinction in Africa in the final 100,000 years was an estimated xx times greater in magnitude as the losses that occurred within the preceding one.5 meg years.

Africa [edit]

Sub-Saharan Africa is the region of the world with the highest amount of Pleistocene megafauna surviving to the present twenty-four hours. These surviving species include the bush-league elephant (Loxodonta africana), the forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis), the blackness rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis), the white rhino (Ceratotherium simum) and the hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius). All of these species maintained populations in sub-Saharan Africa even later on many of them were extirpated from Eurasia during the early Holocene.[58] This means that all of the largest plant eater genera present in Pleistocene Africa are still nowadays today.[59] Overall, estimates as to the proportion of Africa'southward Quaternary megafauna which went extinct range from 5% to 18%, much lower than for all the other continents.[60] [61]

Multiple reasons have been suggested by scientists equally to why Africa apparently had a much milder experience during the Quaternary extinction. Showtime, some take suggested that the Late Quaternary extinction has been comparatively less studied in Africa than in other regions. As a result of this lack of studying, there is little testify that paleontologists are able to depict upon when trying to develop a timeline of extinctions in Sub-Saharan Africa. This hypothesis therefore also argues that further investigation into sites with Belatedly Fourth fossils in Sub-Saharan Africa will reveal previously-undiscovered extinct taxa of African megafauna.[58]

Other scientists have suggested an explanation for the relative lack of extinction among Africa's Pleistocene megafauna which follows the overkill hypothesis as the cause of the Quaternary extinction. Co-ordinate to this hypothesis, many of the extinctions during this time period were due to overhunting by humans who had recently migrated to their continents. In sub-Saharan Africa, the megafauna species had evolved alongside the different species of hominids nowadays in Fourth Africa. As a result, these species had adjusted to withstand the predation pressure level from humans. This meant that both humans and megafauna were able to coexist, and the high levels of extinction seen in the Americas and Australasia were non seen in Africa.[58]

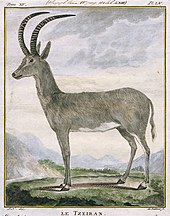

An illustration of a blue antelope (Hippotragus leucophaeus) from 1778.

While i of the pop explanations for the Fourth extinction is due to the changing climate of the fourth dimension menstruation, the climate of Africa has not been suggested as a potential cause. This is because of the high level of megafaunal extinction in S America during this time period. Since Sub-Saharan Africa has almost the same types of climate as Due south America, only South America had many more than extinctions of megafauna taxa, climate was not deemed by these scientists to be a sufficient cause to explicate the relative lack of extinctions in Africa.[58]

Despite the high level of continuity present in Africa'south megafauna community from the Fourth to the Holocene menses, there were several species of megafauna which did go extinct during this time catamenia. Ane such species was Pelorovis antiquus, the Long-horned African Buffalo. This species is theorized to either have gone extinct due to climate change, overhunting by humans, or both. Information technology was extirpated from Sub-Saharan Africa about 12,000 years ago and became entirely extinct about four,000 years before present.[60] Some other was the giant antelope that was very similar to a hartebeest or a wildebeest known as Megalotragus priscus. M. priscus was the last of its genus, and information technology died out approximately 7,500 years ago.[62] Similarly, there was an extinct species of zebra known as the Greatcoat Zebra, Equus capensis. The Cape zebra lived throughout Africa during the Fourth period just went extinct by its cease.[63] One species of Fourth megafauna would also go extinct later on after contact with European settlers, after having its range reduced during the Quaternary extinction event. This species was the blue antelope, Hippotragus leucophaeus. This species had its range restricted changing habitats during the early on Holocene menstruum, so that by the fourth dimension European colonists arrived, they were restricted to one solitary population. This population was then wiped out by habitat loss and hunting past European colonists. The blue antelope went extinct in 1800.[64]

North America [edit]

Size of Megalonyx (a ground sloth) compared to a man

During the American megafaunal extinction consequence, effectually 12,700 years ago, ninety genera of mammals weighing over 44 kilograms became extinct.[65] [66] The Late Pleistocene fauna in North America included giant sloths, brusk-faced bears, several species of tapirs, peccaries (including the long-nosed and flat-headed peccaries), the American lion, behemothic tortoises, Miracinonyx ("American cheetahs", not true cheetahs), the saber-toothed cat Smilodon and the scimitar-toothed cat Homotherium,[67] dire wolves, saiga, camelids such equally 2 species of at present-extinct llamas and Camelops,[68] at least two species of bison, the stag-moose, the shrub-ox and Harlan's muskox, 14 species of pronghorn (of which 13 are now extinct), horses, mammoths and mastodons, the beautiful armadillo and the giant armadillo-like Glyptotherium,[69] and giant beavers, as well every bit birds like behemothic condors and teratorns.

During this megafaunal extinction result, Due north America lost lxx% of its megafauna species. The reasons for the extinction event are still under debate, but it has largely been attributed to both climate change and human-driven extinction.[70] Human-driven extinction is related to the early migrations of Indigenous Peoples to the Americas. There are various human impacts that could accept put pressure on unlike megafauna species, including direct overhunting and cascading trophic interactions. Some researchers attribute the extinction of megafauna to the presence of Clovis hunting, along with significant homo population increases which would have increased hunting intensity and frequency, effectually 13,000 years ago. Contemporaneously, around 12,000 years ago, a global cooling upshot called the Younger Dryas (YD) occurred,[71] which would have dramatically effected habitat area and food sources for many megafaunal species.

The majority of scientists concur that the megafauna extinction in North America was largely caused by both homo-impacts and climatic change since they occurred during the same 5000 year menses.[72] Yet, it can be difficult to generalize an extinction result for the continent as a whole when the climate and homo impacts varied spatially, temporally, and seasonally so it is difficult to generalize what triggered the consequence for the entire continent.[seventy] Thus, it is important to consider that the causes can significantly vary for dissimilar species and different regions of Northward America. The extinction of megafauna and first appearance of humans did not completely correlate beyond North America, meaning that each area needs to be separately considered when attempting to determine the cause of extinction.

Megafauna extinctions that are about consistent with man activity in North America are of the mammoth, horse, and saber-toothed cat. Humans straight impacted mammoth and horse species past overhunting, while the saber-tooth tiger was pushed to extinction indirectly past humans overhunting of their prey. There are ii species of megafauna whose extinctions announced to have no link to homo hunting, they are the Shasta footing sloth and mastodon.[lxx]

Alaska [edit]

Alaska is situated in the northwestern near part of North America. Megafauna disappeared from these college latitudes mostly earlier than the rest of North America. This means that the megafauna in the region either went extinct locally or migrated south as a result of the YD cooling event. Megafauna species disappeared from Alaska approximately chiliad to 4000 years earlier there was significant human presence in Alaska, indicating that their demise probable resulted from climate change.[72] [73]

The Great Lakes Region [edit]

Megafauna species disappeared from Great Lakes Region considerably more recently than in higher latitudes, similar Alaska. Additionally, the first appearances for man species were considerably older for this region compared to other regions in Northward America. Due to the overlaps of these two appearances, it has been suggested from the fossil record that humans and megafauna overlapped in the region for 7000 years.[72] However, the presence of humans does not hateful that the megafauna extinction event in the region was solely attributed to human impacts. There has been significant evidence into the crusade of extinction in this area existence related to the fact that both climate change and homo impacts hit simultaneously.[73]

The West/Pacific Declension [edit]

The Pacific Coast was one of the region where early Ethnic Peoples first migrated. This is due to the fact that humans may take migrated further south from Alaska through a pathway that went along the Pacific Declension. However, there appears to have been lilliputian overlap between humans and megafauna species in these region. One potential for this could exist due to poor sampling due to sea-level rise that could have "obscured older coastal sites".[72]

Indigenous Knowledge of Pleistocene Megafauna [edit]

Indigenous knowledge of Pleistocene megafauna has survived via oral tradition and representations such equally petroglyphs.[74]

The Cayuse people of the Pacific Northwest has oral traditions and a dance centered effectually a story of mammoths migrating into their land. On the Umatilla Indian Reservation, where the Cayuse people lived historically and today, ii mammoth teeth were discovered during construction of a golf game grade.[75]

An Osage tradition tells about a battle between mastodons and mammoths in the Great Plains region. This battle left many animals expressionless and later the battle was over the Osage burned the dead animals. Later, after the Osage were forceable moved to a reservation, white settlers establish mastodon[76] and mammoth[77] basic at this site.

Throughout western Due north America, there are many stories of large, black-winged birds, known equally thunderbirds, which interacted with Indigenous people in both positive and negative ways.[78] These stories of thunderbirds share similarities with species from the genus Teratornis, which are constitute throughout fossil tape of the west coast.[79]

South America [edit]

Reconstruction of a lagoon in central Chile during the late Pleistocene.

About ten,000 years ago, the landscape of South America independent numerous species of megafauna, many of which have no modernistic species for comparison. South America was dwelling house to bears, sabertooth cats, big capybaras and llamas. Additionally, there were huge terrestrial sloths, armored glyptodonts (like to an armadillo, merely the size of a hippo), and animals similar to camels and rhinoceroses (macrauchenids and toxodonts). These animals went extinct during the Quaternary Period and all Southward American mammal species larger than 100 kg were lost. The explanation for their extinction has non been definitively answered, and is a topic of debate among scientists.[eighty]

The continent of South America was isolated for millions of years during the Cenozoic Flow, which had a significant touch on its wild animals.[81] This isolation helped foster species that were not institute anywhere else on Globe. Approximately 3 million years ago, the Great American Biotic Interchange occurred due to the Isthmus of Panama, which immune for the mixing of North and Southward American faunas. The mixing of faunas created new opportunities for expansion, competition, and replacement of species.[eighty] Due south American wild animals in the Pleistocene varied greatly; an instance is the giant ground sloth, Megatherium.[82] The continent besides had quite a few grazers and mixed feeders such as the camel-like litoptern Macrauchenia, Cuvieronius, Doedicurus, Glyptodon, Hippidion and Toxodon. There were also Stegomastodons, establish as far south as Patagonia.[83] The principal predators of the region were Arctotherium and Smilodon. Earlier the interchange Phorusrhacids(terror birds) were also major predators.

Eurasia [edit]

As with South America, some elements of the Eurasian megafauna were similar to those of North America. Amongst the most recognizable Eurasian species are the woolly mammoth, steppe mammoth, straight-tusked elephant, European hippopotamuses, aurochs, steppe bison, cave lion, cavern carry, cave hyena, Homotherium, Irish elk, behemothic polar bears, woolly rhinoceros, Merck's rhinoceros, narrow-nosed rhinoceros, and Elasmotherium. In contrast, today the largest European state mammal is the European bison or wisent.

By the advent and proliferation of modernistic humans (Human being sapiens) circa 315,000 BP,[84] [85] [86] the most mutual species of the genus Homo in Eurasia were the Denisovans and Neanderthals (fellow H. heidelbergensis descendants), and Homo erectus in East asia.[87] Human being sapiens is the only species of the genus Human that remains extant.

Extinction Analysis [edit]

Two major events towards the terminate of the Pleistocene era had ultimately impacted the species that were inhabiting Eurasia; the last glacial period and the introduction of Human being Sapiens from One-time Earth Africa. These two events were responsible for the vastly selective and intense extinctions of the Eurasian large mammal species mentioned previously.[88] The megafauna extinctions that occurred towards the terminate of the Pleistocene is believed to be largely due to human hunting and overkill. Overkill models that incorporate prey availability for Man Sapiens take provided solid backing to that theory.

Hunters of the Upper Paleolithic had crafted tools and projectile weapons that were able to bring down prey every bit large every bit Mammoths. With the population of humans rapidly increasing, the consumption and hunting of meat grew just equally chop-chop. In addition to the growing numbers of human hunters, large terrestrial mammals in Eurasia had to combat detrimental climatic changes.

Northern Eurasia during the Centre and Upper Pleistocene (ca. 700000–10000 BP) was continuously facing a changing climate. The mural and habitats of mammals saw phases ranging from extensive glaciation and common cold stages to temperate climates and interglacials.

A majority of extinctions occurred during the Belatedly glacial (ca. 15000–10000 BP) periods. This period was characterized by a major reformation of vegetation, mainly the replacement of open vegetation past forests. These changes were more profound than earlier in the Terminal Cold Stage and are believed to accept played a critical role in the extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna. [89]

Australia [edit]

The most recent Ice Historic period occurred during the Pleistocene, and caused lower global bounding main levels.[90] [91] The lower sea level revealed the entire Sahul Shelf, connecting Commonwealth of australia with New Guinea and Tasmania.[91] Almost literature about Australian megafauna during the Pleistocene refers to the entirety of Sahul.

Commonwealth of australia was characterized by marsupials, monotremes, crocodilians, testudines, monitors and numerous large flightless birds. Pleistocene Australia also supported the behemothic brusque-faced kangaroo (Procoptodon goliah), Diprotodon (a giant wombat relative), the marsupial king of beasts (Thylacoleo carnifex), the flightless bird Genyornis, the five-meter long serpent Wonambi and the behemothic monitor lizard Megalania.[92] [93] Since 450 Ka, 88 Australian megafauna species have gone extinct.[94]

In that location are several hypotheses that try to explain why Pleistocene Australian megafauna went extinct. Nearly studies bespeak to either climate change or human being activity as reasons for the dice off, but there is not yet a consensus among scientists about which factor had a larger bear upon. A scarcity of reliably dated megafaunal bone deposits has made it hard to construct timelines for megafaunal extinctions in sure areas, leading to a divide amid researches nearly when and how megafaunal species went extinct.[95] [96]

Several studies provide evidence that climatic change acquired megafaunal extinction during the Pleistocene in Australia. Ane group of researchers analyzed fossilized teeth found at Cuddie Springs in southeastern Australia. By analyzing oxygen isotopes, they measured aridity, and by analyzing carbon isotopes and dental microwear texture analysis, they assessed megafaunal diets and vegetation.[94] During the center Pleistocene, southeastern Commonwealth of australia was dominated past browsers, including fauna that consumed C4 plants.[94] By the late Pleistocene, the C4 plant dietary component had decreased considerably. This shift may have been caused past increasingly arid weather, which may have acquired dietary restrictions. Other isotopic analyses of eggshells and wombat teeth also point to a refuse of C4 vegetation after 45 Ka. This refuse in C4 vegetation is coincident with increasing aridity. Increasingly arid conditions in southeastern Australia during the late Pleistocene may take stressed megafauna, and contributed to their decline.[94]

Human activity may have caused Australian megafaunal extinction during the Pleistocene, although this idea is hotly debated. In order to determine whether humans acquired an extinction, iii criteria must be met: (1) if megafauna species went extinct before a significant climate event but later on human colonization, researchers tin can infer that the extinction was probably caused by humans; (2) if climate change during the studied epoch was non more meaning than climate change during previous epochs, then any extinctions during that time were probably not caused by climatic change; and (3) if all or almost megafauna was nevertheless extant when humans arrived, then information technology is possible that man activeness caused the extinction.[97]

Some researchers believe that humans were probably not responsible for the megafaunal extinctions in Sahul. They contribute the extinctions to climate alter, and argue that near megafaunal species do non appear in the fossil tape within 95 Ka of human arrival.[97] Additionally, they claim that long-term aridification of the continent resulted in staggered losses beginning past 130 Ka, and continued range contractions and extinctions throughout the rest of the Pleistocene.[97] Researchers who exercise not believe that man actions were the primary cause of Pleistocene megafaunal extinctions in Commonwealth of australia exercise non exclude anthropogenic influence entirely. One article cites evidence of homo interactions with megafauna at Cuddie Springs, but further explains that humans can only be held accountable for declines in the populations of the 13% of species that can be placed at that location. They debate that it will remain futile to make up one's mind the primary cause of megafaunal extinctions.[97] Other researchers contend that, for almost species, archaeological prove of human being hunting activity is rare and questionable.[98] The major exception to this is the giant bird, Genyornis. Between 54 and 47 Ka, distinct charring patterns on Genyornis eggshells indicate that humans heated the eggs over campfires. This time menstruum besides corresponds to the decline and extinction of Genyornis. Similar charring patterns were found on emu eggs from widespread locations, too dating to this fourth dimension menstruum. These widespread charred eggshells betoken the inflow and fast spread of humans in Sahul.[98] Despite the prove of interactions between humans and Genyornis, there is non much evidence to indicate that there were meaning interactions between humans and other megafaunal species. Many scientists interpret this lack of evidence of interaction as testify that humans did not cause most megafaunal extinctions in Australia.

Other researchers disagree, and debate that in that location is sufficient evidence to determine that homo activity was the master crusade for many of the megafaunal extinctions. They argue that the lack of evidence of hunting does non bespeak that hunting during the Pleistocene was negligible. Rather, archaeological evidence of hunting of animals that went extinct soon after homo arrival should exist negligible, even if that hunting had an ecological impact.[98] Because humans arrived on the continent so early, the period of interaction between humans and megafauna is very small relative to the entire archaeological record of Sahul. Furthermore, hunting rates would have been highest soon later the arrival of humans, when megafaunal populations were very big. Human populations would have been pocket-size during this fourth dimension, and equally a result, would not be as visible in the archaeological record.[98] Researchers who believe that human being activity was the principal cause of megafaunal extinction in Australia argue that the lack of evidence should not rule out human-megafauna interactions.

Insular [edit]

Skull of Canariomys bravoi (Tenerife giant rat). It was an owned species that is now extinct.

Many islands had a unique megafauna that became extinct upon the arrival of humans more recently (over the terminal few millennia and standing into recent centuries). These included dwarf woolly mammoths on Wrangel Island, St. Paul Island and the Aqueduct Islands of California;[99] giant birds in New Zealand such equally the moas and Hieraaetus moorei (a giant hawkeye); numerous species in Madagascar: behemothic ground-habitation lemurs, including Megaladapis, Palaeopropithecus and the gorilla-sized Archaeoindris, three species of hippopotamuses, two species of behemothic tortoises, the Voay-crocodile and the giant bird Aepyornis; five species of giant tortoises from the Mascarenes; a dwarf Stegodon on Flores and a number of other islands; land turtles and crocodiles in New Caledonia; giant flightless owls and dwarf ground sloths in the Caribbean;[100] [101] giant flightless geese and moa-nalo (giant flightless ducks) in Hawaii; and dwarf elephants and dwarf hippos from the Mediterranean islands. The Canary Islands were likewise inhabited by an endemic megafauna which are now extinct: giant lizards (Gallotia goliath), giant rats (Canariomys bravoi and Canariomys tamarani)[102] and giant tortoises (Geochelone burchardi and Geochelone vulcanica),[103] among others. On the California Channel Islands, it is unclear whether humans caused the extinction of pygmy mammoths (Mammuthus exilis), the simply species of megafauna which inhabited the area.[104] Mammoth populations were in refuse on the Channel Islands at the time of man inflow.[104]

See also [edit]

- Holocene extinction

- Megafauna

- Quaternary extinction event

- Walking with Beasts

- Monsters We Met

- Monsters Resurrected

- Before We Ruled the Earth

- A Species Odyssey

- Pleistocene rewilding

References [edit]

- ^ Pavelková Řičánková, Věra; Robovský, Jan; Riegert, Jan (2014). "Ecological Structure of Recent and Last Glacial Mammalian Faunas in Northern Eurasia: The Example of Altai-Sayan Refugium". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e85056. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...985056P. doi:ten.1371/periodical.pone.0085056. PMC3890305. PMID 24454791.

- ^ a b Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (UN). "IPCC Fourth Assessment Report: Climate Change 2007 - Palaeoclimatic Perspective". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 2015-x-30. Retrieved 2015-08-09 .

- ^ a b Clark, P. U.; Dyke, A. S.; Shakun, J. D.; Carlson, A. Eastward.; Clark, J.; Wohlfarth, B.; Mitrovica, J. X.; Hostetler, S. Due west.; McCabe, A. M. (2009). "The Last Glacial Maximum". Scientific discipline. 325 (5941): 710–4. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..710C. doi:x.1126/science.1172873. PMID 19661421. S2CID 1324559.

- ^ Elias, Scott A.; Brusque, Susan Chiliad.; Nelson, C. Hans; Birks, Hilary H. (1996). "Life and times of the Bering land bridge". Nature. 382 (6586): 60. Bibcode:1996Natur.382...60E. doi:10.1038/382060a0. S2CID 4347413.

- ^ Jonathan Adams. "Europe during the last 150,000 years". Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, United states of america. Archived from the original on 2005-11-26.

- ^ Meltzer, David J. (2015-10-21). "Pleistocene Overkill and Due north American Mammalian Extinctions". Annual Review of Anthropology. 44 (1): 33–53. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-102214-013854. ISSN 0084-6570.

- ^ Stuart, Anthony John (1999). "Late Pleistocene Megafaunal Extinctions". Extinctions in Most Fourth dimension. pp. 257–269. doi:ten.1007/978-ane-4757-5202-1_11. ISBN978-i-4419-3315-7.

- ^ Dale Guthrie, R. (2004). "Radiocarbon show of mid-Holocene mammoths stranded on an Alaskan Bering Bounding main island". Nature. 429 (6993): 746–749. Bibcode:2004Natur.429..746D. doi:10.1038/nature02612. PMID 15201907. S2CID 4394371.

- ^ Reumer, Jelle Due west. F.; Rook, Lorenzo; Van Der Borg, Klaas; Post, Klaas; Mol, Dick; De Vos, John (2003). "Tardily Pleistocene survival of the saber-toothed true cat Homotheriumin northwestern Europe". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23: 260–262. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2003)23[260:LPSOTS]ii.0.CO;2.

- ^ Barnett, R.; Shapiro, B.; Barnes, I. A. N.; Ho, Due south. Y. W.; Burger, J.; Yamaguchi, N.; Higham, T. F. G.; Wheeler, H. T.; Rosendahl, West.; Sher, A. V.; Sotnikova, Yard.; Kuznetsova, T.; Baryshnikov, One thousand. F.; Martin, L. D.; Harington, C. R.; Burns, J. A.; Cooper, A. (2009). "Phylogeography of lions (King of beasts ssp.) reveals three distinct taxa and a late Pleistocene reduction in genetic diverseness". Molecular Environmental. eighteen (8): 1668–1677. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04134.x. PMID 19302360. S2CID 46716748.

- ^ Ghezzo, Elena; Rook, Lorenzo (2015). "The remarkable Panthera pardus (Felidae, Mammalia) record from Equi (Massa, Italy): Taphonomy, morphology, and paleoecology". 4th Science Reviews. 110: 131–151. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.12.020.

- ^ Cooper, A.; Turney, C.; Hughen, K. A.; Brook, B. W.; McDonald, H. G.; Bradshaw, C. J. A. (2015). "Abrupt warming events drove Late Pleistocene Holarctic megafaunal turnover". Science. 349 (6248): 602–6. Bibcode:2015Sci...349..602C. doi:10.1126/scientific discipline.aac4315. PMID 26250679. S2CID 31686497.

- ^ White, T. D.; Asfaw, B.; Degusta, D.; Gilbert, H.; Richards, Thousand. D.; Suwa, Yard.; Clark Howell, F. (2003). "Pleistocene Man sapiens from Eye Awash, Federal democratic republic of ethiopia". Nature. 423 (6941): 742–7. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..742W. doi:10.1038/nature01669. PMID 12802332. S2CID 4432091.

- ^ "A Homo Journey:Migration Routes". The genographic project. National Geographic Guild. 2015. Retrieved 12 Baronial 2015.

- ^ Benazzi, Due south.; Douka, M.; Fornai, C.; Bauer, C. C.; Kullmer, O.; Svoboda, J. Í.; Pap, I.; Mallegni, F.; Bayle, P.; Coquerelle, M.; Condemi, Southward.; Ronchitelli, A.; Harvati, Thousand.; Weber, G. W. (2011). "Early dispersal of modern humans in Europe and implications for Neanderthal behaviour". Nature. 479 (7374): 525–8. Bibcode:2011Natur.479..525B. doi:10.1038/nature10617. PMID 22048311. S2CID 205226924.

- ^ Higham, T.; Compton, T.; Stringer, C.; Jacobi, R.; Shapiro, B.; Trinkaus, E.; Chandler, B.; Gröning, F.; Collins, C.; Hillson, S.; o'Higgins, P.; Fitzgerald, C.; Fagan, One thousand. (2011). "The primeval show for anatomically modernistic humans in northwestern Europe". Nature. 479 (7374): 521–4. Bibcode:2011Natur.479..521H. doi:10.1038/nature10484. PMID 22048314. S2CID 4374023.

- ^ Pavlov, Pavel; Svendsen, John Inge; Indrelid, Svein (2001). "Human presence in the European Chill nearly 40,000 years ago". Nature. 413 (6851): 64–7. Bibcode:2001Natur.413...64P. doi:ten.1038/35092552. PMID 11544525. S2CID 1986562.

- ^ "Mamontovaya Kurya:an enigmatic, about 40000 years old Paleolithic site in the Russian Chill" (PDF).

- ^ Pitulko, V. 5.; Nikolsky, P. A.; Girya, E. Y.; Basilyan, A. Due east.; Tumskoy, V. E.; Koulakov, S. A.; Astakhov, Due south. Due north.; Pavlova, Eastward. Y.; Anisimov, Yard. A. (2004). "The Yana RHS Site: Humans in the Arctic Before the Last Glacial Maximum". Scientific discipline. 303 (5654): 52–6. Bibcode:2004Sci...303...52P. doi:ten.1126/science.1085219. PMID 14704419. S2CID 206507352.

- ^ Pitulko, V. V.; Tikhonov, A. N.; Pavlova, E. Y.; Nikolskiy, P. A.; Kuper, K. Eastward.; Polozov, R. North. (2016). "Early human presence in the Arctic: Bear witness from 45,000-year-quondam mammoth remains". Science. 351 (6270): 260–three. Bibcode:2016Sci...351..260P. doi:ten.1126/scientific discipline.aad0554. PMID 26816376. S2CID 206641718.

- ^ Tamm, E.; Kivisild, T.; Reidla, M.; Metspalu, M.; Smith, D. M.; Mulligan, C. J.; Bravi, C. Grand.; Rickards, O.; Martinez-Labarga, C.; Khusnutdinova, E. Thousand.; Fedorova, South. A.; Golubenko, Grand. 5.; Stepanov, V. A.; Gubina, M. A.; Zhadanov, S. I.; Ossipova, Fifty. P.; Damba, L.; Voevoda, K. I.; Dipierri, J. E.; Villems, R.; Malhi, R. Southward. (2007). Carter, Dee (ed.). "Beringian Standstill and Spread of Native American Founders". PLOS ONE. 2 (nine): e829. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..829T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000829. PMC1952074. PMID 17786201.

- ^ Potter, Ben A.; Baichtal, James F.; Beaudoin, Alwynne B.; Fehren-Schmitz, Lars; Haynes, C. Vance; Holliday, Vance T.; Holmes, Charles East.; Ives, John W.; Kelly, Robert L.; Llamas, Bastien; Malhi, Ripan S. (2018-08-03). "Current show allows multiple models for the peopling of the Americas". Science Advances. iv (8): eaat5473. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.5473P. doi:ten.1126/sciadv.aat5473. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC6082647. PMID 30101195.

- ^ Balter, M (iv July 2013). "Farming Was So Dainty, It Was Invented at Least Twice". Scientific discipline.

- ^ a b Malhi, Yadvinder; Doughty, Christopher E.; Galetti, Mauro; Smith, Felisa A.; Svenning, Jens-Christian; Terborgh, John Westward. (2016-01-26). "Megafauna and ecosystem part from the Pleistocene to the Anthropocene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (4): 838–846. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113..838M. doi:ten.1073/pnas.1502540113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC4743772. PMID 26811442.

- ^ a b c Gill, Jacquelyn L.; Williams, John W.; Jackson, Stephen T.; Lininger, Katherine B.; Robinson, Guy Due south. (2009-11-20). "Pleistocene Megafaunal Collapse, Novel Plant Communities, and Enhanced Burn Regimes in North America". Science. 326 (5956): 1100–1103. Bibcode:2009Sci...326.1100G. doi:10.1126/scientific discipline.1179504. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 19965426. S2CID 206522597.

- ^ Tóth, Anikó B.; Lyons, S. Kathleen; Barr, Westward. Andrew; Behrensmeyer, Anna One thousand.; Blois, Jessica L.; Bobe, René; Davis, Matt; Du, Andrew; Eronen, Jussi T.; Faith, J. Tyler; Fraser, Danielle (2019-09-20). "Reorganization of surviving mammal communities after the end-Pleistocene megafaunal extinction". Science. 365 (6459): 1305–1308. Bibcode:2019Sci...365.1305T. doi:10.1126/science.aaw1605. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 31604240. S2CID 202699089.

- ^ Monteath, Alistair J.; Gaglioti, Benjamin V.; Edwards, Mary E.; Froese, Duane (2021-12-28). "Belatedly Pleistocene shrub expansion preceded megafauna turnover and extinctions in eastern Beringia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 118 (52): e2107977118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2107977118. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 8719869. PMID 34930836.

- ^ a b c d eastward Gill, Jacquelyn L. (March 2014). "Ecological impacts of the l ate Q uaternary megaherbivore extinctions". New Phytologist. 201 (4): 1163–1169. doi:10.1111/nph.12576. ISSN 0028-646X. PMID 24649488.

- ^ Karp, Allison T.; Religion, J. Tyler; Marlon, Jennifer R.; Staver, A. Carla (2021-eleven-26). "Global response of burn down activity to late Quaternary grazer extinctions". Science. 374 (6571): 1145–1148. Bibcode:2021Sci...374.1145K. doi:10.1126/science.abj1580. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 34822271. S2CID 244660259.

- ^ Bråthen, Kari Anne; Pugnaire, Francisco I; Bardgett, Richard D (Dec 2021). "The paradox of forbs in grasslands and the legacy of the mammoth steppe". Frontiers in Environmental and the Environment. 19 (10): 584–592. doi:x.1002/fee.2405. ISSN 1540-9295. S2CID 230614023.

- ^ a b c d eastward Johnson, C.n. (2009-07-22). "Ecological consequences of Late Quaternary extinctions of megafauna". Proceedings of the Royal Social club B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1667): 2509–2519. doi:ten.1098/rspb.2008.1921. PMC2684593. PMID 19324773.

- ^ Murchie, Tyler J.; Monteath, Alistair J.; Mahony, Matthew Eastward.; Long, George S.; Cocker, Scott; Sadoway, Tara; Karpinski, Emil; Zazula, Grant; MacPhee, Ross D. E.; Froese, Duane; Poinar, Hendrik Northward. (2021-12-08). "Plummet of the mammoth-steppe in central Yukon as revealed past aboriginal environmental DNA". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 7120. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.7120M. doi:ten.1038/s41467-021-27439-half dozen. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC8654998. PMID 34880234.

- ^ a b c d Galetti, Mauro; Moleón, Marcos; Jordano, Pedro; Pires, Mathias M.; Guimarães, Paulo R.; Pape, Thomas; Nichols, Elizabeth; Hansen, Dennis; Olesen, Jens G.; Munk, Michael; de Mattos, Jacqueline Southward. (May 2018). "Ecological and evolutionary legacy of megafauna extinctions: Anachronisms and megafauna interactions". Biological Reviews. 93 (2): 845–862. doi:ten.1111/brv.12374. PMID 28990321. S2CID 4762203.

- ^ a b Kistler, Logan; Newsom, Lee A.; Ryan, Timothy M.; Clarke, Andrew C.; Smith, Bruce D.; Perry, George H. (2015-12-08). "Gourds and squashes ( Cucurbita spp.) adapted to megafaunal extinction and ecological anachronism through domestication". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences. 112 (49): 15107–15112. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11215107K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1516109112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC4679018. PMID 26630007.

- ^ Spengler, Robert Northward.; Petraglia, Michael; Roberts, Patrick; Ashastina, Kseniia; Kistler, Logan; Mueller, Natalie G.; Boivin, Nicole (2021). "Exaptation Traits for Megafaunal Mutualisms every bit a Gene in Plant Domestication". Frontiers in Establish Scientific discipline. 12: 649394. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.649394. ISSN 1664-462X. PMC8024633. PMID 33841476.

- ^ Smith, Felisa A.; Elliott, Scott Thousand.; Lyons, South. Kathleen (June 2010). "Methyl hydride emissions from extinct megafauna". Nature Geoscience. 3 (6): 374–375. Bibcode:2010NatGe...iii..374S. doi:10.1038/ngeo877. ISSN 1752-0908.

- ^ Marc A. Carrasco, Anthony D. Barnosky, Russell W. Graham Quantifying the Extent of North American Mammal Extinction Relative to the Pre-Anthropogenic Baseline plosone.org Dec 16, 2009

- ^ Nickerson, Colin (September 25, 2007), "Cosmic blast may have killed off megafauna Scientists say early humans doomed, too", Boston.com, Boston, MA: The Boston Globe, p. A2

- ^ Firestone, R. B.; West, A.; Kennett, J. P.; Becker, L.; Bunch, T. E.; Revay, Z. S.; Schultz, P. H.; Belgya, T.; Kennett, D. J.; Erlandson, J. K.; Dickenson, O. J. (2007-x-09). "Show for an extraterrestrial impact 12,900 years ago that contributed to the megafaunal extinctions and the Younger Dryas cooling". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences. 104 (41): 16016–16021. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10416016F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706977104. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC1994902. PMID 17901202.

- ^ Sweatman, Martin B. (2021-07-01). "The Younger Dryas impact hypothesis: Review of the impact evidence". Globe-Scientific discipline Reviews. 218: 103677. Bibcode:2021ESRv..21803677S. doi:x.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103677. ISSN 0012-8252. S2CID 236231169.

- ^ a b Boissoneault, Lorraine. ""Are Humans to Blame for the Disappearance of Earth'south Fantastic Beasts?"". Smithsonian . Retrieved 2019-11-24 .

- ^ MacDonald, James (2018-05-fourteen). "What Actually Happened to the Megafauna". JSTOR Daily . Retrieved 2019-eleven-24 .

- ^ a b Vignieri, S. (25 July 2014). "Vanishing fauna (Special issue)". Scientific discipline. 345 (6195): 392–412. Bibcode:2014Sci...345..392V. doi:10.1126/science.345.6195.392. PMID 25061199.

Although some contend persists, most of the bear witness suggests that humans were responsible for extinction of this Pleistocene animate being, and nosotros go along to drive creature extinctions today through the destruction of wild lands, consumption of animals as a resource or a luxury, and persecution of species we see as threats or competitors.

- ^ a b Cooper, Alan; Turney, Chris; Hughen, Konrad A.; Brook, Barry West.; McDonald, H. Gregory; Bradshaw, Corey J. A. (2015-08-07). "Abrupt warming events drove Tardily Pleistocene Holarctic megafaunal turnover". Scientific discipline. 349 (6248): 602–606. Bibcode:2015Sci...349..602C. doi:10.1126/science.aac4315. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 26250679. S2CID 31686497.

- ^ Sandom, Christopher; Faurby, Søren; Sandel, Brody; Svenning, Jens-Christian (4 June 2014). "Global tardily Quaternary megafauna extinctions linked to humans, not climatic change". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 281 (1787): 20133254. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.3254. PMC4071532. PMID 24898370.

- ^ Faurby, Søren; Svenning, Jens-Christian (2015). "Historic and prehistoric human‐driven extinctions have reshaped global mammal diversity patterns". Diversity and Distributions. 21 (ten): 1155–1166. doi:ten.1111/ddi.12369. hdl:10261/123512. S2CID 196689979.

- ^ Smith, Felisa A.; et al. (Apr 20, 2018). "Body size downgrading of mammals over the late Quaternary". Science. 360 (6386): 310–313. Bibcode:2018Sci...360..310S. doi:10.1126/science.aao5987. PMID 29674591.

- ^ Koch, Paul Fifty.; Barnosky, Anthony D. (2006). "Tardily Quaternary Extinctions: State of the Debate". Annual Review of Ecology, Development, and Systematics. 37: 215–250. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132415. ISSN 1543-592X. JSTOR 30033832. S2CID 16590668.

- ^ Miller, Gifford; Magee, John; Smith, Mike; Spooner, Nigel; Baynes, Alexander; Lehman, Scott; Fogel, Marilyn; Johnston, Harvey; Williams, Doug; Clark, Peter; Florian, Christopher (2016-01-29). "Man predation contributed to the extinction of the Australian megafaunal bird Genyornis newtoni ∼47 ka". Nature Communications. seven (ane): 10496. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710496M. doi:ten.1038/ncomms10496. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC4740177. PMID 26823193.

- ^ van der Kaars, Sander; Miller, Gifford H.; et al. (January 20, 2017). "Humans rather than climate the master cause of Pleistocene megafaunal extinction in Australia". Nature Communications. eight: 14142. Bibcode:2017NatCo...814142V. doi:10.1038/ncomms14142. PMC5263868. PMID 28106043.

- ^ a b c d e "Oldowan and Acheulean Stone Tools | Museum of Anthropology". anthromuseum.missouri.edu . Retrieved 2021-05-07 .

- ^ Hoag, Colin; Svenning, Jens-Christian (2017-10-17). "African Environmental Modify from the Pleistocene to the Anthropocene". Annual Review of Environment and Resources. 42 (one): 27–54. doi:x.1146/annurev-environ-102016-060653. ISSN 1543-5938.

- ^ a b Faith, J. Tyler; Rowan, John; Du, Andrew; Barr, W. Andrew (July 2020). "The uncertain case for homo-driven extinctions prior to Human sapiens". Quaternary Enquiry. 96: 88–104. Bibcode:2020QuRes..96...88F. doi:10.1017/qua.2020.51. ISSN 0033-5894. S2CID 225566468.

- ^ Organized religion, J. Tyler (2014). "Belatedly Pleistocene and Holocene mammal extinctions on continental Africa". Earth-Science Reviews. 128: 105–121. Bibcode:2014ESRv..128..105F. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2013.10.009.

- ^ "Palaeontology and geological context of a Eye Pleistocene faunal assemblage from the Gladysvale Cave, South Africa". Palaeontologia Africana. 38: 99–114. Retrieved 2021-05-07 .

- ^ Rowland, Teisha (19 December 2009). "Aboriginal American Giants Extinct Megafauna of North and South America". Santa Barbara Independent . Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- ^ Martin, Paul Southward (22 October 1966). "Africa and Pleistocene overkill" (PDF). Nature. 212 (5060): 339–342. Bibcode:1966Natur.212..339M. doi:10.1038/212339a0. S2CID 27013299. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d Stuart, Anthony John (May 2015). "Belatedly Fourth megafaunal extinctions on the continents: a short review: Late Quaternary MEGAFAUNAL EXTINCTIONS". Geological Journal. 50 (3): 338–363. doi:10.1002/gj.2633. S2CID 128868400.

- ^ Stuart, Anthony J. (1991). "Mammalian Extinctions in the Late Pleistocene of Northern Eurasia and North America". Biological Reviews. 66 (four): 453–562. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1991.tb01149.10. ISSN 1469-185X. PMID 1801948. S2CID 41295526.

- ^ a b Grand., Martin, Paul Due south. (Paul Schultz), 1928- Klein, Richard (1995). Fourth extinctions : a prehistoric revolution. University of Arizona Press. ISBN0-8165-1100-4. OCLC 851043302.

- ^ Barnosky, A. D. (2004-10-01). "Assessing the Causes of Late Pleistocene Extinctions on the Continents". Science. 306 (5693): 70–75. Bibcode:2004Sci...306...70B. doi:10.1126/scientific discipline.1101476. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 15459379. S2CID 36156087.

- ^ Turvey, Samuel T. (2009-05-28), "Holocene mammal extinctions", Holocene Extinctions, Oxford University Press, pp. 41–62, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199535095.003.0003, ISBN978-0-19-953509-v , retrieved 2021-05-07

- ^ Churcher, C. S. (January 2006). "Distribution and history of the Cape zebra ( Equus capensis ) in the Quarternary of Africa". Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa. 61 (2): 89–95. doi:10.1080/00359190609519957. ISSN 0035-919X. S2CID 84203907.

- ^ Kerley, Graham I. H.; Sims-Castley, Rebecca; Boshoff, André F.; Cowling, Richard M. (2009-04-28). "Extinction of the blue antelope Hippotragus leucophaeus: modeling predicts non-viable global population size as the primary driver". Biodiversity and Conservation. 18 (12): 3235–3242. doi:ten.1007/s10531-009-9639-x. ISSN 0960-3115. S2CID 40104332.

- ^ O'Keefe FR, Fet EV, Harris JM. 2009. Compilation, scale, and synthesis of faunal and floral radiocarbon dates, Rancho La Brea, California. Contrib Sci 518: 1–16

- ^ O'Keefe, F. Robin, Folder, Wendy J., Frost, Stephen R., Sadlier, Rudyard W., and Van Valkenburgh, Blaire 2014. Cranial morphometrics of the dire wolf, Canis dirus, at Rancho La Brea: temporal variability and its links to nutrient stress and climate. Palaeontologia Electronica Vol. 17, Outcome 1;17A; 24p; [ane]

- ^ Fifty. D. Martin. 1998. Felidae. In C. Thou. Janis, K. One thousand. Scott, and 50. L. Jacobs (eds.), Development of Tertiary Mammals of North America i:236-242

- ^ R. M. Nowak. 1991. Walker's Mammals of the World. Maryland, Johns Hopkins Academy Press (edited volume) II

- ^ "North American Glyptodon". Archived from the original on June 24, 2006. Retrieved July ii, 2014.

- ^ a b c Broughton, Jack M.; Weitzel, Elic M. (2018). "Population reconstructions for humans and megafauna suggest mixed causes for Due north American Pleistocene extinctions". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 5441. Bibcode:2018NatCo...nine.5441B. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07897-1. PMC6303330. PMID 30575758.

- ^ Rasmussen, S. O.; Andersen, Grand. Yard.; Svensson, A. M.; Steffensen, J. P.; Vinther, B. M.; Clausen, H. B.; Siggaard-Andersen, K.-L.; Johnsen, S. J.; Larsen, L. B.; Dahl-Jensen, D.; Bigler, M. (2006). "A new Greenland ice cadre chronology for the last glacial termination". Journal of Geophysical Enquiry. 111 (D6): D06102. Bibcode:2006JGRD..111.6102R. doi:ten.1029/2005JD006079. ISSN 0148-0227.

- ^ a b c d Emery-Wetherell, Meaghan M.; McHorse, Brianna K.; Byrd Davis, Edward (2017). "Spatially explicit analysis sheds new light on the Pleistocene megafaunal extinction in North America". Paleobiology. 43 (4): 642–655. doi:10.1017/pab.2017.15.

- ^ a b Barnosky, A. D.; Koch, P. L.; Feranec, R. S.; Wing, S. Fifty.; Shabel, A. B. (2004). "Assessing the Causes of Late Pleistocene Extinctions on the Continents". Science. 306 (5693): 70–75. Bibcode:2004Sci...306...70B. doi:x.1126/science.1101476. PMID 15459379. S2CID 36156087.

- ^ Steeves, Paulette F. C. (2021). "Affiliate 1: Decolonizing Indigenous Histories". The Indigenous Paleolithic of the Western Hemisphere. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Printing. p. 163. ISBN978-1-4962-0217-viii. OCLC 1263182142.

- ^ Cultural Resource Protection Program (March 2000). "A Review of Oral History Information of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation". Department of Natural Resources, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation.

- ^ Montagu, M. F. Ashley (1944). "An Indian Tradition Relating to the Mastodon". American Anthropologist. 46 (four): 568–571. doi:ten.1525/aa.1944.46.4.02a00250. ISSN 0002-7294.

- ^ Cruikshank, Julia (1980). Fable and mural : convergence of oral and scientific traditions with special reference to the Yukon Territory, Canada. Scott Polar Research Institute. OCLC 70618191.

- ^ Hall, Mark A. (2004). Thunderbirds America's living legends of giant birds. New York: Paraview Press. ISBNane-931044-97-10. OCLC 493870454.

- ^ Steeves, Paulette F. C. (2021). "Chapter 7: Genetics, Linguistics, Oral Traditions, and Other Supporting Lines of Evidence". The Indigenous Paleolithic of the Western Hemisphere. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. p. x. ISBN978-1-4962-0217-8. OCLC 1263182142.

- ^ a b Samonds, Karen E. (2014-12-01). "Megafauna: Giant Beasts of Pleistocene South America". Journal of Mammalogy. 95 (half dozen): 1308–1309. doi:10.1644/fourteen-MAMM-R-132. ISSN 0022-2372.

- ^ Webb, South. David (August 2006). "The Great American Biotic Interchange: Patterns and Processes1". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 93 (two): 245–257. doi:10.3417/0026-6493(2006)93[245:TGABIP]ii.0.CO;2. ISSN 0026-6493.

- ^ A. E. Zurita, A. A. Carlini, Thou. J. Scillato-Yané and Due east. P. Tonni. (2004). Mamíferos extintos del Cuaternario de la Provincia del Chaco (Argentina) y su relación con aquéllos del este de la región pampeana y de Chile. Revista geológica de Chile 31(1):65-87

- ^ O. P. Recabarren, M. Pino, K. T. Alberdi. (2014). La Familia Gomphotheriidae en América del Sur: evidencia de molares al norte de la Patagonia chilena. Estudios Geológicos, Vol 70, No 1.

- ^ Gunz, Philipp; Harvati, Katerina; Benazzi, Stefano; Cabec, Adeline Le; Bergmann, Inga; Skinner, Matthew M.; Neubauer, Simon; Freidline, Sarah E.; Bailey, Shara E. (June 2017). "New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Human sapiens" (PDF). Nature. 546 (7657): 289–292. Bibcode:2017Natur.546..289H. doi:10.1038/nature22336. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 28593953.

- ^ Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Ben-Ncer, Abdelouahed; Bailey, Shara E.; Freidline, Sarah East.; Neubauer, Simon; Skinner, Matthew Thousand.; Bergmann, Inga; Le Cabec, Adeline; Benazzi, Stefano (2017-06-07). "New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Man sapiens" (PDF). Nature. 546 (7657): 289–292. Bibcode:2017Natur.546..289H. doi:10.1038/nature22336. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 28593953.

- ^ "These Early on Humans Lived 300,000 Years Ago—But Had Modern Faces". 2017-06-07. Retrieved 2017-10-13 .

- ^ Kaifu, Yousuke (2017). "Primitive Hominin Populations in Asia before the Arrival of Modern Humans: Their Phylogeny and Implications for the Southern Denisovans". Electric current Anthropology. 58 (17): 418–433. doi:10.1086/694318. S2CID 149397030 – via Academy of Chicago Press.

- ^ Carotenuto, F. (July 1, 2018). "The well-behaved killer: Late Pleistocene humans in Eurasia were significantly associated with living megafauna only". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 500: 24–32. Bibcode:2018PPP...500...24C. doi:ten.1016/j.palaeo.2018.03.036. PMC5263868. PMID 28106043.

- ^ Stuart, Anthony (Nov 1991). "Mammalian Extinctions in the Late Pleistocene of Northern Eurasia and N America". Biological Reviews. 66 (4): 453–566. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1991.tb01149.x. PMID 1801948. S2CID 41295526.

- ^ Zimmermann, Kim Ann (29 August 2017). "Pleistocene Epoch: Facts Most the Concluding Ice Age". livescience.com . Retrieved 2021-05-05 .

- ^ a b Hirst, One thousand. Kris. "What Did Australia Look Like When the First People Arrived?". ThoughtCo . Retrieved 2021-05-05 .

- ^ "Australia's Megafauna". Archived from the original on 2018-03-24. Retrieved 2008-12-17 .

- ^ Death of the Megafauna

- ^ a b c d DeSantis, Larisa R. Thou.; Field, Judith H.; Wroe, Stephen; Dodson, John R. (2017-01-26). "Dietary responses of Sahul (Pleistocene Australia–New Guinea) megafauna to climate and environmental change". Paleobiology. 43 (2): 181–195. doi:ten.1017/pab.2016.50. ISSN 0094-8373.

- ^ David, Bruno; Arnold, Lee J.; Delannoy, Jean-Jacques; Fresløv, Joanna; Urwin, Chris; Petchey, Fiona; McDowell, Matthew C.; Mullett, Russell; Mialanes, Jerome; Wood, Rachel; Crouch, Joe; Berthet, Johan; Wong, Vanessa N.L.; Greenish, Helen; Hellstrom, John; GunaiKurnai Land; Waters Aboriginal Corporation (2021-02-01). "Late survival of megafauna refuted for Cloggs Cave, SE Australia: Implications for the Australian Belatedly Pleistocene megafauna extinction debate". Quaternary Scientific discipline Reviews. 253: 106781. Bibcode:2021QSRv..25306781D. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106781. ISSN 0277-3791. S2CID 234010059.

- ^ Toll, Gilbert J.; Zhao, Jian-xin; Feng, Yue-Xing; Hocknull, Scott A. (2009-02-01). "New U/Th ages for Pleistocene megafauna deposits of southeastern Queensland, Australia". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 34 (two): 190–197. Bibcode:2009JAESc..34..190P. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2008.04.008. ISSN 1367-9120.

- ^ a b c d Wroe, Stephen; Field, Judith (2006-11-01). "A review of the evidence for a human function in the extinction of Australian megafauna and an culling interpretation". 4th Science Reviews. 25 (21–22): 2692–2703. Bibcode:2006QSRv...25.2692W. doi:ten.1016/j.quascirev.2006.03.005. ISSN 0277-3791.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, C. N.; Alroy, J.; Beeton, N. J.; Bird, M. I.; Brook, B. W.; Cooper, A.; Gillespie, R.; Herrando-Pérez, Due south.; Jacobs, Z.; Miller, Yard. H.; Prideaux, M. J. (2016-02-ten). "What caused extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna of Sahul?". Proceedings of the Imperial Guild B: Biological Sciences. 283 (1824): 20152399. doi:ten.1098/rspb.2015.2399. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC4760161. PMID 26865301.

- ^ Extinct dwarf elephants from the Mediterranean islands Archived 2009-01-23 at the Wayback Car;

- ^ North American Extinctions v. Globe

- ^ Mammoths and Humans as tardily Pleistocene contemporaries on Santa Rosa Island, Found for Wildlife Studies 6th California Islands Symposium, Larry D. Agenbroad, et al, December 2003. Retrieved 8 November 2015

- ^ Algunas extinciones en Canarias Archived 2009-12-28 at the Wayback Auto Consejería de Medio Ambiente y Ordenación Territorial del Gobierno de Canarias

- ^ «La Paleontología de vertebrados en Canarias.» Spanish Periodical of Palaeontology (antes Revista Española de Paleontología). Consultado el 17 de junio de 2016.

- ^ a b Rick, Torben C.; Hofman, Courtney A.; Braje, Todd J.; Maldonado, Jesús E.; Sillett, T Scott; Danchisko, Kevin; Erlandson, Jon One thousand. (2012-03-01). "Flightless ducks, giant mice and pygmy mammoths: Late Quaternary extinctions on California's Aqueduct Islands". World Archeology. 44 (1): 3–twenty. doi:10.1080/00438243.2012.646101. ISSN 0043-8243. S2CID 161764677.

External links [edit]

- "Ice Age Bay Area". Archived from the original on 2008-12-26. Retrieved 2011-05-28 .

- "The Extinct Tardily Pleistocene Mammals of North America". PBS.

- "End of the Big Beasts". PBS. Archived from the original on 2012-05-14. Retrieved 2017-09-08 .

- "Of mice, mastodons and men: human-mediated extinctions on 4 continents" (PDF).

- "Return to the Ice Age: The La Brea Exploration Guide". Archived from the original on 2011-08-12.

- "Large Collection of European Ice Historic period Megafauna Fossils: The Earth Museum of Human Collection". Archived from the original on 2013-03-29.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pleistocene_megafauna

Posted by: garciajusture70.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Which Animal Is Most To Blame For The Loss Of Forests In Southwest Asia And North Africa?"

Post a Comment